A New Mode of Affluence

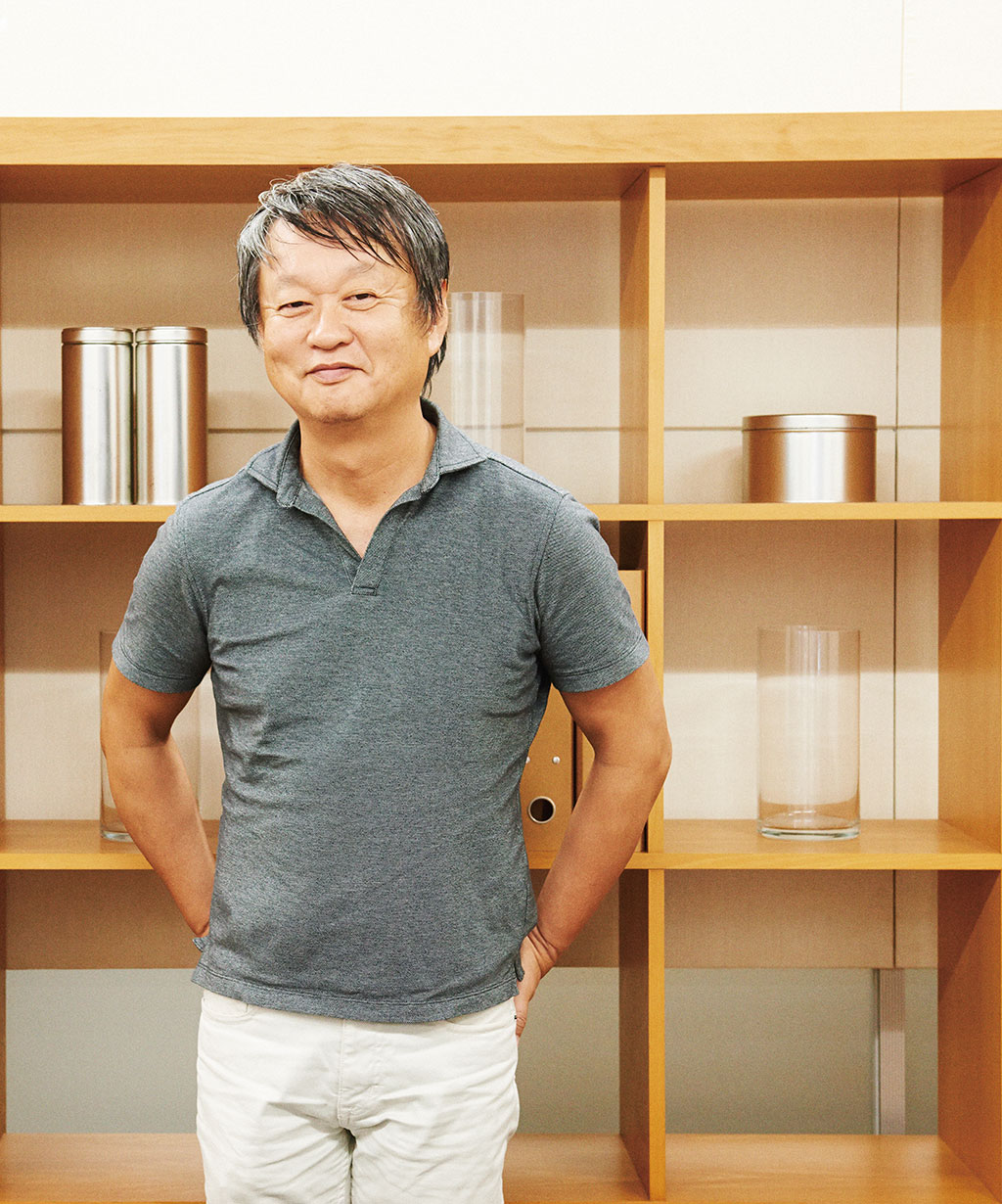

Naoto FukasawaProduct Designer

The more we prioritize function and efficiency, the more richness we lose.

In an Age Saturated with Material Wealth

Internationally acclaimed product designer, Naoto Fukasawa has had a hand in the development of numerous products and a variety of projects since 2002 as a MUJI advisory board member.

Fukasawa is known for designs that integrate just enough function with absolute minimal form. He considers not only the relationship between behavior and object, but he delves into observing the space in which that relationship is formed. It is in this process that his products, with a simple and minimalist tatazumai (the presence of an object), are born.

How does Fukasawa see the Compact Life concept proposed by MUJI?

“The concept of the MUJI brand came about in an age when the Japanese economy had grown rapidly and people were enjoying material wealth. So, in the original concept, there was a very strong element of having one’s day-to-day needs already met. This was an attitude formed because people were saturated with material wealth, and in this sense, [the Compact Life concept] shows a return to our origins. At the same time, I think the concept accurately captures the direction in which today’s society is moving.”

Storage as Walls, Function as Extension of the Body

The environment in which we live has gradually changed as homes and household appliances have evolved and information technology has developed. Fukasawa evaluates these changes in terms of “walls and bodies.” He says that most of the tools we use every day without thinking tend to evolve into extensions of either our walls or our own bodies.

He explains: “The clearest example of this is the television. Old TVs were cathode-ray sets, which took up a great deal of space. This evolved to liquid crystal displays with very thin screens, and TVs can now be embedded in walls or hung on them. On the other hand, we can also watch video now on palm-sized smart phones and tablets. The latter are examples of objects that have evolved into extensions of our bodies.”

Looking at our living spaces today in these terms is enlightening for just how many objects fit his description — air conditioning and lighting fixtures embedded in ceilings, kitchen appliances housed in wall cabinets.

“We are gradually moving toward a world in which form will disappear and only function will remain. Things will continue to move in this direction. As a result, it should be possible in the future to live without material objects at all. However, the more we prioritize function and efficiency, the more richness we lose. And at that point, we find objects whose presence cannot be contained as extensions of a wall or of our bodies.”

Fukasawa says that when he designed products for European and North American manufacturers in the past, he appreciated their approach to design in which every detail — not only the design of the specific piece of furniture — was thoroughly discussed. If it were a table, what would sit on it? If it were shelves, what kind of books would they hold and how would they be arranged? This focus seems to view product design as one aspect of ambient design — designing furniture as part of the process of designing the space as a whole.

Fukasawa says that when he designed products for European and North American manufacturers in the past, he appreciated their approach to design in which every detail — not only the design of the specific piece of furniture — was thoroughly discussed. If it were a table, what would sit on it? If it were shelves, what kind of books would they hold and how would they be arranged? This focus seems to view product design as one aspect of ambient design — designing furniture as part of the process of designing the space as a whole.

On Ambient Design

“I recently remodeled the closet in my house. In the process, I looked carefully at each jacket that would hang in it. I selected only the best jackets and the ones I love to wear. I kept only about half of what I had owned, and this gave me a great deal more room — about 10 centimeters between hangers. At first glance, it doesn’t appear as if anything exists in between my jackets, but the fact is the empty space is there; it is present. By adding this void space, I redesigned how the closet works as a whole, including the invisible, but very real flow of the space.”

A well-designed life is not simply a matter of fewer possessions, or of organizing things and storing them well. What is important is to identify for oneself those objects whose presence cannot be contained as extensions of a wall or of our bodies and to bring these objects into the workings of our daily lives. For example, calling attention to the beautiful emptiness of a particular space on a shelf by placing a rock found while traveling or a piece created by a master craftsperson there. The Japan Folk Crafts Museum, where Fukasawa serves as director, is surely a great resource in this respect.

“Objects that are totally ordinary, but that age in just the right way, captivate us. This happens, doesn’t it? These objects have a richness that is the polar opposite from material wealth, and perhaps that is why they are so captivating. As the elements of our daily life evolve into extensions of either the wall or our bodies, the idea of Compact Life describes a style of incorporating spaces that feel to us personally as bits of luxury.”