Takashi SugimotoTakashi Sugimoto Works for MUJI

A lot came to mind as I looked around at everything this morning in preparation for today’s opening of the Shanghai MUJI store.Since the first MUJI store opened some 30 years ago, the basic concept has not changed.

For this store, we built a ship installation on the first floor. I wanted a ship to represent a certain fundamental aspect of the human experience. Setting aside whether or not it works, we have created a space that has the MUJI “flavor” in this most bustling city of Shanghai. I believe this flavor is unlikely to change in the future and that it is important that we make sure that it does not change.

The first MUJI store opened in 1983, a little over 30 years ago. It was a fairly small store, and it was from this small space that MUJI started. The biggest difference between then and now is that MUJI didn’t have as many products. Since the first store, we grew to the hundreds of stores we have now. But we still use the same materials, and our concepts have not changed.

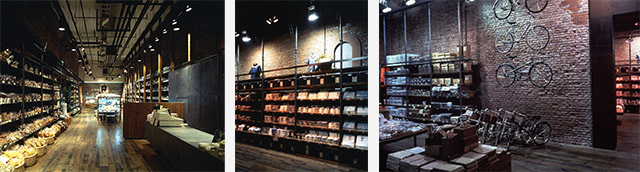

The store in Sapporo (1993), which was one of our early stores, was opened on the site of a refurbished old factory with its brick walls and other elements. This site is larger than our first MUJI store, and the layout is more organized and products are easier to find, so it may feel a bit pristine. We later felt that our original concepts of what MUJI should be and the energy it should have were lost somewhat.

This is MUJI in Aoyama Sanchome (1993).

This is also one of the early stores, and at 1,000 m2, it was a large flagship store for us. But it is quite a bit smaller than the Shanghai store. This is the store that finally got us to our target sales figures.

MUJI’s first phase was completed, and sales gradually rose, so management felt that MUJI had reached a significant milestone.

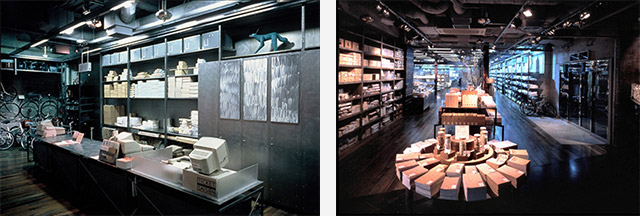

Now we skip quite a bit ahead to MUJI in Shinjuku (2008). For the store’s restaurant, Café&Meal MUJI, we created a lighting fixture made of wine glasses, inspired by the chandelier. At this store, we reached a high level of completion in terms of products. We began debating among ourselves what the next generation of MUJI was to be. By this time, a large number of MUJI staff were involved in planning. I myself felt that the design had gotten a bit too perfect, and I wanted to get away from that a bit.

We knew that MUJI’s place in the market meant competing with more expensive brand name products and also with other companies’ reasonably priced products. This is not a matter of fussing over prices. It is that what MUJI sells, basically, are products. Our products are the medium through which our message is delivered to our customers. The message of the MUJI concept must be expressed as much as possible through the products.

Products may end up going off on their own. For example, say we sell a certain product in our stores this summer and then again next year. We can’t always sell the exact same thing. So we end up perfecting products… trying to add a competitive edge to a product. When the number of products increases and they sell well, these products end up moving on their own toward perfection. They take on a life of their own. A certain “allure” that doesn’t naturally exist with a single product is inevitably present when products are set in rows on store shelves.

This is an age of overwhelming commercialism. It’s not just MUJI; other manufacturers, too, are adding allure to their products. Although allure in and of itself is a positive thing, I felt somehow that we didn’t need to add artificial allure to MUJI. This temptation is not specific to other brands; I am sure MUJI has the potential to do the same since it is pervasive in our world. With MUJI surrounded by brand name products, this is something that I am very much afraid of, a real danger. For this reason, we must constantly define what MUJI is and stay vigilant against this temptation.

MUJI started with small stores of about 100 – 130 m2 and has gradually expanded floor space with more products and more and more customers over 30 years. The Yurakucho flagship store (2011) is a kind of picture of what we have been aiming for.

And now we have opened our Shanghai flagship store. I believe that our experience with how Shanghai grows and changes will shed some light on what the next generation of MUJI will be.

---Question1

If it proves difficult either technically or financially to create in China the design you have prepared, do you then change the design? Have you ever experienced this?

There seems to be little difference these days between Japan and China in terms of technical skill. When I worked in Shanghai, a very long time ago, it was quite difficult. It was very difficult to have the blueprints understood accurately, and there were sometimes complete misunderstandings. This isn’t true anymore. When we meet to discuss blueprints, the work is nearly exactly as planned. In some cases, I ask Japanese contractors for help. When working in Southeast Asia, I’ve also had contractors from Shanghai. Differences according to national identity are nearly gone, I think.

This may be straying slightly from your question, but I don’t believe that the work of a designer figures much into the costs of the project. Design will cost money on one level or another, no matter who the designer is. There may be some designers who are skilled at very expensive designs, but I think there are more designers who are the opposite. We, too, focus on relatively low-cost design.

This is true not only for me. I think most designers are focused on this.

---Question2

Of all the MUJI stores built since the first one, which is your favorite?

I don’t really rank the stores first or second like that. In fact, I always like the latest one the best. So my favorite now is MUJI Shanghai Huaihai 755. Besides Shanghai, there are two or three stores that I have profound, fond memories of. But, each of these stores was part of our progression, so I am most fond of the modern store we have built now.

---Question2-2

What is it that you like about this store? What do you wish was a little better? Do you have any regrets?

I always have a long list of regrets when I finish any project, but I like the ship. I designed it because I liked it, of course, but when I saw it finished, I really thought “Wow!”

---Question3

In China, they say, “MUJI isn’t sexy.” What are your thoughts on this?

I see it a little differently. MUJI has a MUJI type of sexiness. This is a different sexiness than the high-end brands. I think there are people who get this and people who don’t. I think sexiness varies depending on the era, the society, and the individual. Looking at the fashions young actresses are wearing today, we seem to be moving away from the glamorous sexiness that we used to see. I’m not saying this is good or bad. I just think this is the way society is changing.

---Question4

You said earlier that the Shinjuku store was “too perfect.” Is there a gap between what you yourself think is good and how the store turned out?

The theme I most want to address in all of my work is “living life.”For example, you go to the morning market out in the countryside. There are the vegetables and fish, but there are also people meeting and chatting. This is the natural appeal of living life, and it is what most attracts my attention. Not only in Japan. It’s true in the rural areas of every country that I have visited. It brings warmth to life. You buy a little something, have a bit to drink and eat. I think, more than anything else, this is where we find the pleasure of life.

Needless to say, for MUJI, it all comes down to the products we sell. We have to sell products, and to do that, we have to keep prices down and get rid of the frills. For example, MUJI curry sells for about 400 yen. It’s not an expensive item. We’ve thought, “Why not sell curry for 1,000 yen? Why not sell curry for 800 yen?” And I imagine you’ve thought this, as well. MUJI works hard so that the curry can be sold for 400 yen. The situation would be different, though, if the price were 500 yen or 800 yen. We would use different ingredients and market it differently. But we have decided to sell it now for 400 yen, and this is why we are competitive. It is not just MUJI. For example, in Japan, you can eat soba for less than 300 yen at noodle stands. But, why not charge 500 yen or 800 yen? Because customers would likely stop buying the soba. This is the conventional wisdom of our society, and the fact that we conform to these standards is, I think, one of commercialism’s weaknesses. One does become unable to pull away from society’s typical standards. I think this is a bit misguided.

What is the difference between lighting in a brand name store and lighting at MUJI?

I don’t think I have an answer, because it is related to the talent and skills of the person in charge of lighting. It’s not a matter of what is good or bad, but a difference in how much effort the lighting person makes and how hard he or she works.

Are you satisfied with the lighting at this store?

Yes, I am 70 to 80% satisfied with it.

What do you focus on most when designing a store?

This is the hardest part, but I focus on the flow of the space. The strongest analogy for this is a bar. You have the bottles, the whiskey, and the customers. I myself drink whiskey. But I’m not thinking about the name of the whiskey or how strong the lighting is when I drink. Most of all, I think about how I feel in the place I’m sitting at the bar. If I get a good feeling, I’m happy to stay. If it feels bad, I’ll probably leave quickly. That is the crux of design, I think.

How will the design of future stores change?

I’ll talk about how it is changing now. I think our concept is becoming more and more solidified. Take for example, this space here where we’re all meeting today. We’d have to say the interior design of this room is not especially good. It serves its purpose, but it doesn’t have a nice feeling about it. There is not a sense of uniqueness about this space. It’s not a matter of, for example, changing the wallpaper.

It’s not a matter of adding a chandelier. If you look at rooms from the Middle Ages, the walls were not papered; they were made of wood. Chandeliers with candles hung from the ceilings, and these elements were thought to be grand. But, today, we don’t really get that feeling from those same elements.

This is a story I heard when I went to the Mediterranean Sea. In Nice, in the middle of town, not on the coast, there is a bar with a sand-covered floor. I walked in, went to the counter, and sat down. The bartender looked at me with a smile and said, “This sand is not from Nice.” But he said, “This sand was brought here from the African coast.” Across from Nice in Africa is Morocco and Tunisia. The sand was brought by ship from those countries to be used on the floor. I don’t know if the story is true or not. But it does tell us something. I thought, “So this is sand that was walked on by Moroccans.”

It is not a big thing, but it leaves an impression. I think this story is important when we talk about the space we are in now.

Nowadays Japanese shopping centers are built in suburban areas, not in commercial areas. What I’d like to see in these centers are the values of the people living in that community. I’d like to see a lot of different people in a new place, interacting, “We want to eat this particular dish.” Or “Look, this is what we usually eat.” “This is what we wear.” “That’s what I want to buy.” A town would rise up around a particular market. A history book written in Chinese in the third century touches a bit on markets in Japan. At the time, markets apparently began to strongly influence the people. China is even more amazing, I think, in this respect. For example, the first Emperor of China in the Qin dynasty. There were most likely places for interaction and communication back then, weren’t there? I think of this as the prototype of towns and villages, and for commercialism and commercial society.

This is still happening now, and I think its effects are something we should value.

The MUJI design policy is seemingly consistent store to store, but do you adjust the design for certain areas? If so, what differences are there?

There is no difference.

<

>